Buy the book Growing Up Itchy

The mountain rested. Summer wound down like a falling helicopter seed – spinning its last spins as it rode the breeze. It was a loss of sorts. It could never go back up, but the fall was a beautiful thing.

Ash and Grey were wandering the mountainside, clobbering tall mullein plants with their whacking-sticks. They loved to swing and strike hard, hearing the shoof of their sticks whistling through the thin air and feeling the SMACK of impact. Dried mullein was fun to knock down, and they sometimes did this as an idle pastime while they conversed about other things. The mullein plant was a tall thing, about as tall as Grey. Thin, green stems dried hard in the late summer, and soft, lamb-eared leaves shriveled up and dropped off. Topping the tall stem was a head of something that looked like a small corn cob. Eventually they dried completely, turning dark brown. Seeds clustered in small pods at the top end, waiting for a living creature to blunder by and help them rattle down to the fertile earth below. Grey and Ash with their whacking-sticks were just the thing the mullein needed to sow their future generations.

Grey was about to take a hard swing at another mullein when he heard a long, slow call echoing across the slope. It was Mom – her voice long and drawn out; warped by countless pine trees, fields of grass, and wind. The boys were far from home today, but not too far to be called back.

Grey and Ash paused – whacking-sticks held at the ready. Mom’s distant voice rode the breeze again, and they knew they must go back to the house.

Bare legs flashed and they ran off towards home, speed fueled by hunger. They guessed it had to be near lunchtime by now. Grey’s torso felt as hollow as a banjo. Onward they ran, across hills and ravines, slowing to walk only when the path they followed wound among rocky areas – boulders strewn on the mountainside.

After lunch, Mom put them to work. The days were still long, but the nights were growing colder, and Grey was the designated firewood boy. Dad stacked many short logs between two fir trees near their little house, and it was Grey’s job to split them down to a size that fit into the wood-stove, and carry them inside. Unlike the dreaded chore of carrying water jugs, swinging the ax didn’t hurt his hands. He was usually never grumpy when it was time to chop wood. It wasn’t bad, as chores went.

Grey selected a round log of pine from the stack and held it in his hands. He looked at the ends; one end was angled and one was flat. So he put the flat end down onto the chopping stump, standing the log on end like a short, fat fence post.

Grey lifted the ax and swung it down. The white pine split easily; ringing loud in a satisfying CRACK. Soon he had an armload of fresh pine-smelling pieces. The plywood floor of the new house creaked as he brought in three loads and dumped them into a pile next to the big stove. It would be plenty warm in the house tonight.

This wood stove was a big metal barrel resting on its side, fitted with a door and a stovepipe. Behind the stove was a partial wall of round river rock. Dad mortared the stones onto the wall one by one, and then he ran out of mortar, or stones; Grey wasn’t sure which. The wall was there to protect the wood house from stove heat. It stood unfinished, but it would have to do. Most of the house was unfinished, but it was better than living in the trailer.

The chores were done and Dad was home now. Ash and Grey played with Bethany, keeping watch over her while Mom finished dinner on the cook-stove. Sometimes the cook-stove would belch out great clouds of smoke. At times, it was finicky and hard to get going. Powered by pine, like the big barrel stove, it needed smaller pieces; and Grey had to bring in wood for that stove too.

They were tucked into bed, nightly prayers were said and a song was sung, at Bethany’s request. The children were soon fast asleep in the little mountain house. Night fell. The Aurora Borealis rose over the northern slopes like a loose green curtain. It floated as if blown by a gentle breeze, but the children were not awake to see it. Mom and Dad were sitting quietly downstairs, and Sally lay on the floor.

* * *

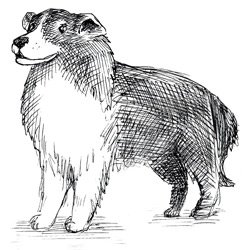

Sally, the black-and-white sheepdog, now occupied the role of family guardian. After Bo’s disappearance, Dad bought young Sally from a farmer down in the valley. She was a different kind of dog; a better kind, as Dad said. She would not enjoy running vast distances as much as Bo did – she was the kind of dog who would want to stay close and guard the family. She was an Australian Sheepdog.

Sally started her life as a wonderful, lovable puppy. She was destined to be a great guard, but she began her career as a child’s plaything – Grey and his siblings toyed with her endlessly. She was an agreeable pup, content to be carried around, prodded, petted and snuggled daily.

Her young life was not all sweet-smelling roses, however. She did, on occasion, find herself in some sticky situations.

With no running water, the family did not have a toilet in the house. Whenever Grey or Ash had to go to the bathroom at night, they’d tiptoe downstairs quietly exit the front door, and run at full speed.

The outhouse was far away by a child’s standards. It was a common pit toilet with a small shack erected over it; built thirty yards from the house so as not to bother anyone with unpleasant smells. The distance seemed insignificant during the day, but at night the vastness of the mountainside pressed in, and visions of mountain lions danced in their heads. The cold starlight was just enough to dimly illuminate the outhouse path. As one could imagine, the necessity of leaving one’s warm bed in the middle of the night to run to a distant bathroom was downright onerous, so Grey and Ash always made the trip as quickly as possible. It was best to get the whole thing over with; to make a run for it. They flew over the ground, childish paranoia giving their feet wings. In the winter, bare feet were much faster than slow snowboots – so the boys preferred to speed out and back barefoot. Freezing feet were an acceptable sacrifice to get the whole thing over with more quickly; to get back to one’s snug bed before it cooled.

It was a night such as this when Ash had to make the trip. Grumbling inwardly, he could not hold it any longer. He got up, tiptoed downstairs, and out the front door.

A dark fuzzy blob greeted him, warm fur rubbed against his legs. Sally was a light sleeper, and eagerly crawled out from her nest under the house to see who it was that had come to play.

He reached down to pet her. Feeling the chill, he picked her up, warm and wiggling.

He started to put her back down, but he changed his mind. Holding her tightly, he ran as fast as he could out into the dark, the thirty-yard path seeming more like a mile as Sally bounced in his arms.

He couldn’t move as fast while holding Sally, but she was a comforting presence.

The outhouse had no electricity of course, and it was pitch black inside. This was not a problem for Ash, he knew the place by heart.

“Wait right here, Sally,” Ash said. He set her carefully onto the bench.

Sally wagged her tail, happy to be with a human during a time when she’d normally be sleeping. She did not sit down to wait as Ash expected.

She walked, unseeing, right into the dark hole.

Warm dreams scattered as Grey woke up to shaking. What’s happening?

“Hey!” Ash whispered urgently. Something was wrong – he seemed upset.

“What?” Grey said, sleep thick in his voice.

“It’s Sally!” Ash hissed. “She fell down the outhouse!”

“She fell in the hole?”

“Yeah! What should we do?”

“She fell… into the… sewer?”

“Yes!” Ash whispered. “She fell in!”

Grey rolled into a sitting position. “We have to get Dad,” he muttered.

Dad was not too happy at being awakened, but he found just enough humor in the news to suppress some of the natural grumpiness a person normally would have.

“She fell in the hole?”

“Yeah,” Asher said.

“Why did you take her into the outhouse?”

“She wanted to come,” Ash said with a shrug.

Dad yawned. “OK. Get your shoes on. We have to get her out of there.”

Grey and Ash followed Dad back out across the dark expanse to the outhouse. He held the only electrical device they owned, a shiny metal flashlight. They kept it near the door for special emergencies.

Pointing it down the hole, Dad grunted at the sight. “She’s going to be OK,” he said. “It’s not too far of a drop.”

Sally whined, looking up at them from six feet below.

Grey was worried that Sally would have sunk down into the pile, but he winter had frozen the toilet contents into a rock-hard mass.

Dad looked at them. “Which one of you boys wants to go down to get her? Ash, you’re the smallest.”

Gray and Ash gaped.

Dad’s face grew thoughtful, and he looked at Asher. “I could lower you down, and you could hand her back up. I don’t know if we could get you back out though.”

He paused for effect. The boys stared at him.

Dad chuckled. “I’m joking. Grey, go get me the rope from under the seat of the truck.”

Grey took off for the truck, running into the night. He returned in record time, panting from exertion.

Worry and concern for Sally were still written across Asher’s face, despite Dad’s jokes.

“It could have been a lot worse,” Grey said. “Imagine if it had been warm down there?”

“She would have been in a real heap of… trouble,” Dad said. “Deep trouble.”

He tied a slipknot, making a noose in the rope.

“Grey, hold the flashlight. Do not drop it in!”

Grey held tight to the tin flashlight, pointing it down at Sally’s sad puppy face. Dad lowered the noose into the hole.

“Hold still Sally! Sit!” Dad said..

It was no use. Sally was untrained and would not hold still. She ran back and forth, putting her paws up onto the dirt sides of the hole. She was eager to get out of that smelly, frozen prison.

After a few minutes, Dad gave up. “I can’t get the noose around her. She’s moving too much.” He straightened up, thinking.

“It’s OK, Sally!” Ash called down.

Sally whined from atop the frozen pile.

“Grey, do you have a whacking-stick that would reach down there?” Dad said.

Grey shook his head. “What about one of my skis?”

Dad nodded. “Go get it for me.”

Grey fetched the ski from the house, and Dad tied the noose to the end of it. He reached the ski down to the hole and guided the noose around Sally’s fuzzy neck.

“She’s not going to like this.”

With a careful pull, the noose tightened, and Dad hoisted her up, ignoring her strangling sounds. The boys stood back, eyes riveted on the rescue efforts. Grey still held the flashlight, illuminating Sally as she emerged from the hole. Dad removed the noose as soon as her feet were firmly planted on the bench, and the strangling noises stopped.

They all breathed a collective sigh of relief.

The liberated puppy wagged her tail – she was more than overjoyed to be out of that pit.

She jumped up, putting her paws on Ash, who stepped away quickly, brushing himself off.

“Sally, you stink! Get off me!”

No one volunteered to carry her this time. She had to walk back to the house on her own four paws.

***

Sally was older now, almost full-grown. She raised her head and stared at the door. A long moment passed, then a low “gurf!” rolled from her throat. Dad looked up from his mandolin, where he had been playing a quiet song, tiny notes pausing to listen. Mom stopped knitting, her concentration broken.

“What is it, Sally?” Dad half-whispered, not wanting to wake the children upstairs.

Without further warning, the room suddenly echoed with a burst of noise as Sally began to bark in earnest. She jumped up and paced to and fro, eyes wild; glaring at the door. She barked and growled, baring her teeth. Dad jumped up in alarm.

Mom’s Winchester now in hand, Dad lifted the latch and clicked the door open. Sally bolted out, a streak of black and white fur. Dad followed her, pausing for an instant to grab the emergency flashlight. The kerosene lanterns that lit the house didn’t work too well outdoors, making only a tiny yellow flame. Only the flashlight could pierce the dark out there.

Sally ran a little way up the slope, fur bristling and throat growling low. Dad followed. What’s going on with her? She paused and looked back at Dad, waiting for him. He quietly cycled the Winchester’s action, cocking the sleek, oiled lever forward and back. A bullet slipped smoothly into the chamber; the rifle was ready to fire. The beam of light bounced from the flashlight as he followed Sally up the north slope. The sheep were picketed up there.

Grey woke up the next morning. He had slept fitfully, with a few senseless dreams. The kids usually slept like stones, and none of them were awakened by the racket in the night. He heard Mom and Dad talking downstairs, and he strained to listen. “Sheep” and “mountain lion” were words he could pick out. He got out of bed and went down.

Hard, burnt potatoes rattled across Grey’s plate as he ate. He crunched thoughtfully, wondering about what he had heard. He hated not knowing what was going on when Mom and Dad were acting weird.

“Mom, why were you talking about mountain lions earlier?”

Turning from the cook-stove, Mom looked at him. “Something ate Space last night. Dad’s not sure what it was – some wild animal.”

“Space is dead?” Grey asked.

“Yes,” said Mom. “Dad found part of her carcass, but he couldn’t find whatever animal did it.”

Grey crunched his fried potatoes. He only felt a little bit sad at the loss. Space was pretty dumb, but she was nice, as sheep went. Not his favorite.

The next morning, Mom told him the same thing had happened again. Grey and Ash looked at each other, eyes wide as Mom relayed the tale of how Sally started barking after dark, Dad ran up the hill, and another sheep had been eaten. Dad had tracked the animal all night and he was sure that it was not a mountain lion.

“What was it?” Ash asked.

“Dad thinks maybe a bear,” Mom said.

A bear! Grey didn’t like the thought of that at all. He spent so much time thinking about mountain lions that he never had time to worry about bears. He looked at the door. It didn’t seem safe outside anymore..

“Which sheep got eaten?”

“Scarlet. Don’t worry about it. Go fill the water jugs. There’s only one left and we’ll need a bunch more for dishes tonight.”

Grey sighed. “OK, Mom.”

Scarlet was one of the nicer ewes.

While he never liked the chore, getting water from the spring was something that felt extra troublesome today.

The mountainside felt large and exposed, and he pushed the wheelbarrow as fast as its tipsy bulk could go. It was too easy to imagine that bears watched his movements from the surrounding mountainside. Grey knew every stump, every log, and every rock, but his imagination played tricks on him. Perhaps some of these familiar landmarks could hide the form of a big bear. The rough dirt path from the little plywood house to the spring seemed to stretch on for miles, and the loud rattle of empty plastic jugs bouncing around in the wheelbarrow made him cringe. He didn’t want to make noise; this chore seemed much too loud. Things could hear – and things could come find him. Things like bears.

Today felt like a day suited for being quiet, and watchful.

He filled the jugs unusually fast for a boy who despised the job, wasting no time as he efficiently moved the hose from jug to jug. He re-capped and loaded each into the waiting wheelbarrow while the next one filled. He scanned the aspen grove and low bushes that surrounded the spring.

Jesus, let there be no bears around here. Grey prayed. Simple and to the point.

Then the wheelbarrow blasted down the path back to the house with Grey at the helm. He trotted; almost running, eyes intently watching the trail ahead for hazards. Any loose rock could send the whole load of water jugs smashing down the slope. His forearms ached as he gripped the wheelbarrow’s hardwood handles. He made it back to the house in mere minutes, panting hard. One by one he slid the jugs up into the open doorway, parked the wheelbarrow by the woodpile, and went inside, looking over his shoulder as he did.

Ash played with Bethany on the floor. “Did you see any bears?” Ash asked.

Grey shook his head, and went to the kitchen to give Mom a hug. She bent down to embrace him, and he felt a little better.

“Bears won’t bother us here, Grey,” she whispered to him. “We have Sally and my Winchester. Bears are afraid of people.”

Later that day, Dad came home from work and immediately asked if they had anything to report. They didn’t, no news was good news, but they were all nervous about the coming night.

That evening they sang their song, and said their prayers. Then Mom prayed that God would send the bear while they had light enough to shoot it.

“In Jesus’ name, Amen” Mom finished.

Grey and Ash bolted up from their pillows, startled at sudden barking. Sally was going crazy downstairs. A scramble, a clatter rang out as Dad jumped up from his chair. He stomped into his boots, wasting no time.

***

The Winchester was an expert at waiting. It lived up on its perch above the front door, feeling the door open and close below it. Each day, the house rattled and trembled as the family went about their daily doings, but the Winchester waited. Night would fall, and yet it waited still, ever ready for its ultimate purpose. If the Winchester could think, it would have taken great pleasure in this moment. The very pinnacle of its existence was near; but it was merely oiled steel and polished wood. It could not understand that this could be the day to defeat the foe that threatened the family.

A hand quickly lifted the Winchester from its pegs. Its mindless bulk did not experience a brief disorientation, this new movement – this action – was welcome. The previous two nights had brought the same motion to the Winchester, and each time it was returned to the pegs, un-fired. Energy waited, bound up within the Winchester. Springs were compressed, gunpowder packed tight. Soft gray bullets poised, ready to race forward out the black steel barrel into the wide world.

The dog was below, raising the alarm. The Winchester waited still, firmly in the grasp of its master. Outdoors it flew, then up a hill and into the trees. Evening light played along the Winchester’s smooth walnut stock as Dad stalked the beast in the woods.

A noise was heard, a crashing in the undergrowth as the dog went into a new frenzy of barking. The world shook as Dad ran, then the Winchester aimed. A massive black shape loomed, and Dad squeezed the Winchester’s cold trigger.

The energies bound up inside Winchester shouted out – gleeful and exuberant as they were instantly released. Springs sprung, gunpowder exploded, and bullets soared, freed from their brass shells. Sharp, acrid smoke puffed out into the cooling air.

Once, twice – seven times the Winchester fired, each shot ringing out into the darkening sky. The massive black bear fell and was finally still.

***

The bear was seven feet tall, and loomed large over Grey’s head. Dad hung it from a large pine near the path to the spring. Grey looked up at it, not caring to get too close even though the bear was no longer a danger.

Its paws were as big as dinner plates.

“Too bad we can’t keep it.” Dad said. “I’d like to have some of those claws.”

They could not take any part of the bear, including his meat. A white truck rattled up the drive. It took Dad and the driver ten minutes to get the bear into the back of the truck.

“Who was that?” Asher asked, after the truck took the bear away.

“That was the Game Warden.”

Their big bear belonged to the state now.

“It’s a waste and a shame,” Dad said. “It would have made a nice rug.”

I remember Sally.

There was another time when something was dropped in the black hole and I held Ash by his ankles and lowered him into the black hole so he could grab it.do you remember that?