Buy the book Growing Up Itchy

The mountains rested. Wintertime had come and the aspen leaves waited on the ground to receive their covering of snow. Grey and his family moved down to Curlew, a tiny town at the base of the mountain, where they were to live in a house. Dad said that the egg trailer had no heat, and the house was not yet ready, so they must go stay in town. Their colorful Easter-egg home was traded for a house of old brown bricks, weathered boards, and a sagging porch. It lacked homey charm of any kind, and had certainly seen better days. Grey stared at this house, and frowned. A road, a train trestle bridge, and a river bordered the spot where they would spend the winter. No longer would they hear the watery sound of wind through countless pine needles and aspen leaves, or the distant rolling moo of grazing cows. Not for awhile anyhow – the plan was to move back up to the mountain when winter was over. Grey couldn’t wait to get back.

The family settled in, and eventually white flakes, as big as summer grasshoppers drifted down. The snow-making cloud cover hung heavy overhead. He had seen snow before, once when they lived in California’s Mojave Desert (Dad said that was a rare occurrence and that they were lucky to see it.)

What he saw now, as the first snowfall of the year landed, was nothing like anything he had experienced in his six short years. The snow fell a little, then a little more. Then a lot more, but it wasn’t done yet! It fell, and kept on falling. It soon blanketed the ground, but it wasn’t done yet. It piled up and up, and what a wonder it was. The bleak landscape took on a rounded look that softened the little town into something quite nice to look at.

They played hard in that new snow, rolling it into huge balls like Dad showed them; to make snowmen.

They each wore a dark blue snow coat that puffed out in all directions, and their mittens did not quite keep snow out of their sleeves as they played. But when little boys are having so much fun, just about any amount of cold could be ignored.

Grey had gotten a pair of bright orange skis for his last birthday and was happy to finally use them. The snow was deep now, up to his waist. The world sparkled cold and white as he struggled to unlock the secrets of skiing. He observed that the skis would not work like a sled, the deep snow made them sink – so he stayed on the driveway, where the snow was harder-packed and not as deep. The driveway was not as steep as the mountain, and Grey wondered how much faster he could ski up on the mountain.

Thoughts of the mountain made him miss the animals and the cozy egg trailer. He paused for a moment, staring at the snowflakes.

“Come on, help me pull the sled!” Ash yelled.

Before this winter, Grey had never seen a sled outside of a book, until Dad came home with a toboggan. Such a strange name for a sled – but the sled was as long as the name, so Grey figured it was a good name. The toboggan was almost as long as the boys put together, and made of wood which curled up at one end. It had a yellow rope handle which they used to pull it back up hills. He knew the toboggan would go faster up on the mountain, and he wished they could sled up there instead.

“Dad, can we try out the sled on the mountain sometime?” Grey asked.

“We can’t go up for awhile yet, the roads are too snowed in to drive on,” Dad said.

When Dad saw the look of disappointment on Grey’s face, he added: “We’ll have just as much fun sledding here.”

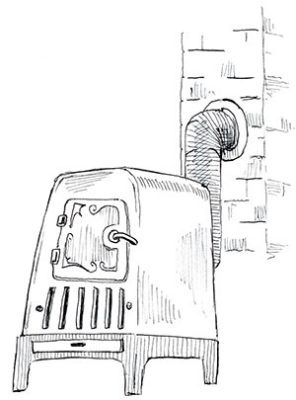

The house they stayed at in town creaked when you walked through it. A large wood-stove in the center of the living room did its best to keep out the cold, aided by many inches of snow on the roof. (Dad explained to him that snow was like a blanket, it helped the house stay warm.) The stove was made of tall, dark iron. It reminded Grey a little of the whale dump truck that brought them up here to Washington, complete with rusty brown spots.

Dad kept that stove roaring hot, and the boys quickly learned to stay away from it. It felt good to warm up after sledding, but once they were toasty, they did not like to be in the same room with it. Sometimes the stove would glow red, and other times it would woof. “Woof, woof, woof” the hulking stove would gasp – and flames would shoot out of the vent holes with each woof.

The stove was craving fresh air. It did not have enough to breathe, and was trying to burn the air out in the living room, the same air the boys were breathing. They were fascinated by this, and would come close to watch.

At night Dad would close the vents and the red angry glow would fade. Grey and Ash were tucked tight into their beds, prayers were said, a song was sung, and consciousness left them almost before their bedroom door closed. A hard day playing in deep snow makes a boy fall asleep in an instant.

Soft fluffy snow filled his eyes, ears, and mouth… he heard yelling. He tried to yell back, but couldn’t! Why was there snow in his mouth? He couldn’t breathe!

With a muffled noise, Grey woke from his nightmare with a gasp. He heard someone out in the hall, shouting. His head, thick with sleep, felt like a pillow stuffed with fur. What was happening? He struggled up and sat on the edge of his bed, then jerked as the door crashed – Dad was there, reaching for Grey, holding him and Ash under each arm. His view spun as they whirled out into the snow.

Mom was in the driveway screaming “Help! Fire! Fire!” and Grey’s blood flowed cold within him.

Hearing the fear in Mom’s voice was worse than anything, worse than the lonely nighttime howl of coyotes, even worse than mountain lions. He had never heard Mom make such a noise before. Ash was sobbing, sleepily at first, but he was waking up now, his cries grew louder, more heartfelt. Dad dropped them off in the snow at Mom’s side and ran back into the house. Mom continued her screams for help, while Grey and Ash clung to her legs. It was as this time Ash realized that he was smelling smoke, and his eyes hurt – he began to wail.

“Mom! Mom!” Grey cried. “What’s happening!”

Mom, out of breath and voice growing hoarse, looked sharply at him and told him that the chimney was on fire. Mom knelt down and held Ash and Grey close. People were running all over the place now, others from town had heard Mom’s cries for help. There were no phones in that old house, but the town was a scant dot on the map, and neighbors were not far. They flew down the road and across snowy fields, running up to them in ones and twos, and soon the boys were put in the truck, safely out of danger. The kind strangers in that little town quickly helped Mom and Dad put out the chimney fire, saving the little house from complete destruction.

***

That spring was a busy one for the family. The small town did not exactly bustle, but sometimes a car would drive past the house, or a train would thunder over the trestle bridge. The trains in those parts carried long logs, huge loads of fallen pines. The trains would trundle the logs up to the sawmill. Grey wanted to see the sawmill someday; he’d like to see all of the big wood-cutting machines.

Dad had sent most of the animals away to live with a farmer, but he brought Caleb and the goat down from the mountain to their town house. Grey stood near the fence-post, patting Caleb as they watched Dad tie the goat in the back yard. Grey liked the goat, and was happy to have it down in town with them. He knew the goat was for food, but it was sometimes difficult not to think of it as a pet. Caleb was happy to see the goat as well, and Grey had to hold him back because the goat and Caleb liked to fight. It was cloudy that day, and Grey could smell the dank, rotten grass patches that were daily growing bigger. He could smell the remains of the burnt chimney, and the memory of the fire made him feel cold. Winter was relaxing into spring.

The bleating of the goat caught his attention again and he decided to go pet it.

“Don’t go falling in love with it now,” Dad said as Grey started to walk over to the goat. “I’m going to butcher it today. We’ll be eating goat meat for a month.”

Grey knew that Dad grew up in San Diego. Dad may have come from the big city, but he was a dreamer; and he wanted to live as the pioneers lived. His idyllic dreams included turning the goat into food.

Grey watched as Dad made his preparations. With the goat securely tied to the fence, Dad approached with an ax handle, three feet of solid hickory wood. Dad had thought carefully about how to dispatch the goat. He figured that the best way would be to quickly break the goat’s neck with a mighty blow. No blood, no suffering.

Dad was talking to the goat as he moved into position. Dad was never one for telling soothing stories, and the goat pranced nervously.

When Dad was ready, certain the goat would hold still for a bit; he swung the ax handle down as hard as he could. It smashed onto the goat’s neck with a bone-banging CRACK.

Grey flinched. The makeshift club bounced, and the goat stood there; puzzled and unharmed. Maybe Grey detected a change in the goat’s mood, maybe he didn’t; he was not sure. Dad was the strongest person he knew, but that goat seemed to be strong too. It didn’t pay much attention to the ax handle, but it was looking at Dad now.

Dad waited for the goat to look the other way, then swung the ax handle down onto the goat’s neck several more times, in quick succession. The goat’s neck was as hard as the bedrock which jutted from the mountainsides. That goat did not want to be food, and it clearly had no intention of dying that day. The goat did however begin to take offense at Dad’s efforts to kill it, and was bleating louder than ever. Mom poked her head out the door, looking annoyed.

“What’s the matter?” she said.

Grey thought she might have been smirking a bit.

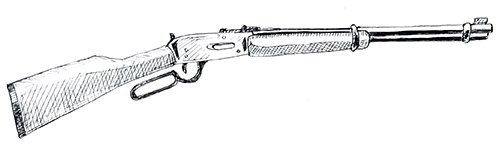

Dad grimly looked at the goat, and it jittered, looking back at Dad, who went inside the house. When he came out, he had the rifle. It was a 30-30 Winchester that he had bought for Mom, but she never used it. Sometimes Grey forgot it belonged to Mom.

“Plug your ears, Grey,” Dad said.

Grey jammed his fingers deep into his ears as Dad took aim. BAM! A burst of smoke and fire accompanied the noise, and the goat jumped. The ground also jumped, dirt spraying up from a hole on the other side of the goat.

Dad muttered something under his breath and aimed the gun again. Grey could not hear what Dad said, and he dared not unplug his ears just yet, not with another shot getting ready to go off. The gun sounded again, sharp and ringing. The jittery goat made a mighty leap, straight up into the sky and landed on the ground, feet running hard. Sharp hooves tore up the rotten winter grass as it blasted across the field, freed from the rope which bound him to the fence post. The rope had been shot clean through. Dad was not too happy.

“This is ridiculous. Hold still, you!” Dad growled at the goat, glancing around. He didn’t want to shoot the rifle too much here in town, he had no desire to involve any neighbors.

After a bit more running, the goat decided to calm down enough to eat some damp grass again; perhaps to build up more energy for more running.

Dad checked the gun. “Go fill the dog bowl,” he said to Grey.

Grey poured some dog food in the dog bowl. Dad took the dog bowl in his free hand and shook it a bit. The goat heard the rattle, and promptly stopped eating grass. The goat – just like Blondie and the hens – loved to eat dog food, and his head shot up. He peered at the house, where Dad and Grey were standing. He could hear the food’s tasty rattle, and thought it would make a nicer snack than last year’s undergrowth.

Grey and Dad stepped back around the far corner of the house as the goat casually sauntered over to the dog bowl. The goat knew he was not supposed to eat the dog food, but no one was stopping him this time, and running a few fast laps around the yard had made him hungry. He nibbled, and looked about. No boys were there to shoo him away with sticks, so he nibbled a little more.

***

As the family ate dinner that night, Mom laughed. “We’ll have to get another bowl for Caleb!” She said.

The dog bowl would never be the same. It had a jagged hole in its side.

The goat was delicious, and Grey thought it was one of the best things he had ever tasted.

The next morning dawned bright, a rare springtime day was blooming. After forcing down his breakfast of oatmeal, Grey went out to see the place in the yard where the goat was butchered. Caleb seemed interested in it too, and came with him.

Grey stood with Caleb, looking down at the spot on the ground. Grey was straddling Caleb’s back, with one foot on each side of him. He absentmindedly patted Caleb while looking at the goat spot. Grey was not riding Caleb like he rode the sheep, but perhaps Caleb did not understand this, because he stopped sniffing the goaty smell.

Blazing fangs and a sudden, deafening growl were all the warning Grey had, as Caleb whirled around and bit Grey right in the face.

The screams and angry barks sent Mom and Dad flying out into the yard in two instants.

Grey cried as he rode in the car with Mom. She was driving with the urgency of a bird fleeing a cat, and Ash was riding in the back seat, solemnly sitting quietly, eyes wide. Grey did not know where Dad was. Mom told him to press the cloth hard to his face, and not to move it.

Crying, and the dog bite, made his face hurt. He could not see from his eye, and was more than a little scared. Why had Caleb attacked him? Confusion swallowed his thoughts as he tried to make sense of it, but he was having a hard time thinking about things clearly, with the hot flowing blood and Mom’s erratic swerving. The road ahead of them wound through the foothills, following the Kettle river like a snake stalking a grasshopper. Treetops flashed by as Grey slumped in the passenger seat of the Datsun, looking up at the sun with his one uncovered eye.

Mom was driving him and Ash to the big town. It was about twenty-five miles away, and Grey knew that it was the only place with a hospital. His arm was growing tired of holding the cloth to his cheek for so long.

That day Grey got his first stitches, eleven of them. They throbbed in a black, prickly row under his right eye. He was still a little scared from the procedure, but the kind, smiling face of Doctor Fergus assured Grey that everything would be OK. The lollipop helped as well. The look of relief was clear on Mom’s face, and on Dad’s when he came home later that evening.

“You’re lucky to keep that eye,” Dad said.

Mom glared at Dad. “You’re going to be fine,” she said soothingly. “God was watching out for you.”

“Were you teasing Caleb?” Dad asked.

“No! I was just standing there with him. I did not even sit down on him!”

Dad frowned. “We’ll never have a dog that bites people. Not on my watch.”

The thought of coming that close to blindness made Grey’s heart quake.

Grey never saw Caleb again, Dad and the Winchester saw to that. They wouldn’t be needing that new dog bowl for quite some time.

0 Comments